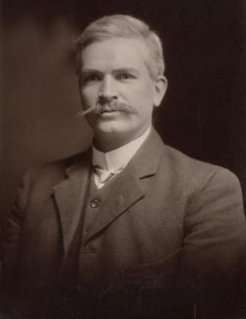

ANDREW FISHER PC 1862–19281

Born in the coalmining village of Crosshouse, near Glasgow in Scotland on 29 August 1862, Andrew Fisher was the second son among the eight children of miner Robert Fisher and Jane, née Garvin. When his father contracted pneumoconiosis, Andrew (still below the legal age of 12) began work in the pits. He gained a basic formal education from the local public school and evening classes at Kilmarnock, making use of a library and reading room at a co‑operative store which had been established by his father and others in Crosshouse in 1863.

Secretary of the Crosshouse district branch of the Ayrshire Miners' Union from age 17, Fisher gained local renown as a leader organising strike action, and was twice blacklisted by mine owners. Wanting greater opportunities but conscious of responsibilities at home, Fisher was ultimately persuaded by his family to emigrate. He and his younger brother, James, arrived in Queensland on the SS New Guinea on 17 August 1885. The brothers first worked on the Burrum coalfields at Torbanlea – where Andrew Fisher was briefly a manager in the Queensland Colliery Company – and from 1888 until the end of 1890 on the goldfields at Gympie.

Prominent in the burgeoning labour movement in Queensland, Fisher was the inaugural secretary of the Gympie Joint Labor Committee and in 1891 became the first president of the Gympie branch of the Workers Political Organisation, part of the Australian Labor Federation which had been formed in Brisbane two years before. Also president of the local branch of the Amalgamated Miners' Association, he was a key figure in major strike action in 1891 and was again blacklisted. Obtaining his engine driver's certificate he took up driving trains, continuing to work at mines, but above-ground.

Heavily involved in the Presbyterian Church, Fisher was a Sunday school superintendent and became a staunch follower of the religion, and a teetotaller, all his life. Also active in other areas of community life he was a member the Royal True Friendship Lodge of the Manchester United Independent Order of Oddfellows, a shareholder in the Gympie Industrial Co-operative Society and, for a time, a member of the local unit of the Colonial Defence Force.

Representing Gympie at Labor-in-Politics Conventions held in Brisbane in the 1890s, Fisher topped the poll for Labor in Gympie in the 1893 Legislative Assembly elections. He lost his seat in 1896, partly because of vocal opposition from the Gympie Times. Employed as an engine driver, and for a period as auditor to the municipal council, he worked with other Labor supporters to found an alternative newspaper, the Gympie Truth, first published in July 1896.

Re-elected to the Legislative Assembly in March 1899, Fisher was influential in the formation of the first Labor government in Australia on 1 December that year. He served as secretary for railways and for public works for the six‑day term of the minority government, which was led by Anderson Dawson. Using the Gympie Truth to promote his causes, including opposition to sending troops to fight in the South African War, Fisher supported and campaigned for federation of the Australian colonies, encouraging a strong local 'yes' vote in the Federation referendum of 1899. Endorsed as the Labor candidate in the new federal electorate of Wide Bay, Fisher won it convincingly at the election on 29 March 1901.

On 8 May 1901 – the day before the opening of the first Commonwealth parliament – the 19 Labor senators and 15 Labor members in the House of Representatives met to found the federal parliamentary Labor Party. John Christian (Chris) Watson was elected leader, and the Party platform was agreed. It included a 'white' Australia, the franchise for women, old age pensions, a citizen army, and the principle of compulsory arbitration in disputes between employers and employees. Thornier questions of fiscal policy and the extent of alliances which should be formed with the governing Liberal Protectionists took longer to resolve. Fisher took the view that, while he was happy to cooperate on programs which accorded with broad Labor policy, the Labor Party should always maintain its identity and independence. A quiet yet confident man, he was determined to succeed but favoured a conciliatory approach to issues. Tall and muscular with a long dark moustache and sandy hair, he did not have the oratorical brilliance of some of his contemporaries and never lost his Scottish accent, but he presented as honest and sincere and won the trust of the electorate and his parliamentary and party colleagues.

At the age of 39, Fisher married 27 year-old Margaret Jane Irvine, his landlady's daughter, at her family home in Cross Road, Gympie on 31 December 1901. In 1902 he travelled to London to attend the coronation of King Edward VII, representing the Australian Labor Party in the contingent led by Prime Minister Edmund Barton.

Responsible for moving his Party's attempted amendments to proposed conciliation and arbitration laws, Fisher was actively involved in the debate on the most contentious bill of the early parliaments. With Labor's numbers increased following the December 1903 election – the first where women in all states could vote on the same basis as men2 – the second Protectionist Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin needed Labor support to stay in government. In April 1904 when an amendment to the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill, moved by Fisher and unacceptable to Deakin, was carried, Deakin resigned. The Labor caucus rejected an offer of coalition with Deakin's supporters, and Watson formed the first federal Labor government. Fisher was appointed Minister for Trade and Customs, an office he held from 27 April until 18 August 1904 when Watson also failed to gain a majority of votes on the Bill and the government fell. Taking advantage of a split amongst the Protectionists earlier that year, Free Trader George Reid then formed a coalition government with one Protectionist group, led by Allan McLean. For the first time, Labor constituted the federal Opposition in its own right.

When Watson resigned in October 1907, Fisher was elected leader of the federal parliamentary Labor Party. By then Labor, despite outnumbering Deakin's followers in the House of Representatives, was supporting the second Deakin government with the hope of achieving some of Labor's priorities, in particular aged pensions, anti-trust laws and 'New Protection' legislation, aimed at protecting local industries from cheap overseas competition. With the Labor caucus increasingly disgruntled with this arrangement, the alliance collapsed, the Deakin ministry resigned and Fisher formed a minority government. He was both Prime Minister and Treasurer from 13 November 1908 until the opening of the next session of parliament on 26 May 1909. During the recess a fusion of the three non-Labor groups in the parliament was negotiated, giving Deakin a majority sufficient to govern. His request for a dissolution refused by the Governor-General, Fisher resigned on 29 May 1909 and served as the leader of the Opposition until the next general election on 13 April 1910. He used the time productively to improve the organisation and more clearly define the policies of the parliamentary Labor Party.

The 1910 election resulted in a decisive victory for Labor, which became the first federal party to win a clear majority in both chambers. Fisher's second term as Prime Minister and Treasurer commenced on 29 April 1910. His government left a legacy of reforms and national development which included establishment of the Royal Australian Navy, the Commonwealth Bank, the Inter-State Commission and the Department of the Prime Minister; expansion of the High Court bench to seven judges; the transfer of the Northern Territory to Commonwealth control; the founding of the national capital at Canberra; and commencement of construction of the trans-Australian railway line. Workers' compensation for Commonwealth employees and more liberal old-age pensions were provided, maternity allowances introduced and the goal of greater political equality for women espoused.

Fisher travelled to Pretoria in October 1910 for the inauguration of the Union of South Africa; and to London in May 1911 to attend the Imperial Conference, where he attracted some interest as the only Labor prime minister present. Attending the coronation of King George V during the same visit, Fisher, who eschewed decorations of any kind, reluctantly accepted the new King's offer of appointment as a Privy Councillor (PC). Accorded a hero's welcome on a visit to his birthplace in Scotland, Fisher was made a freeman of the burgh there.

Three advices in the Opinion Book were signed by Fisher as acting Attorney-General during 1912, when the deputy leader of the parliamentary Labor Party, Billy Hughes, held that portfolio. Relating to citizen defence forces, inclusion of items in appropriation acts and use of the Australian Blue Ensign, all three opinions were published in Volume 1.

Seeking to extend Commonwealth power over trade and commerce and industrial relations in the State railway services – and to enable it to make laws with respect to corporations, trusts, monopolies and various industrial matters – Fisher's second government developed six referendum proposals. Put to the electorate at the same time as the May 1913 elections, all six were defeated by narrow margins and Labor lost government to Joseph Cook's Liberals by one seat. Surviving subsequent leadership challenges, including one from Hughes, Fisher generally managed to maintain a constructive working partnership with his dynamic deputy. He was, however, starting to show the strain of leading a restive parliamentary party – and of being the father of six young children.

Characterised by legislative deadlocks and political jousting, the Fifth Parliament ended in the first federal double dissolution in June 1914. Engaged in intensive campaigning for the September election when confronted with the outbreak of the First World War on 4 August 1914, both party leaders were agreed on their commitment to the Empire, Fisher making the memorable pledge of support to the 'last man and last shilling'. Following a resounding electoral victory, Fisher began his third term as Prime Minister and Treasurer on 17 September 1914. Responsible for dispatching the first Australian troops overseas for service in the First World War, and for providing financial foundations for the war, he did so without conscription, which he did not support. He also instituted the rule of preference being given to returned soldiers in public service employment. Worried by the exclusion of Australia from policy decisions on the war, and in failing health, Fisher resigned from parliament on 27 October 1915 and was replaced by Hughes as party leader and Prime Minister. Appointed High Commissioner for Australia in London from 1 January 1916, Fisher made his Melbourne home, Oakleigh Hall, available as a convalescent home for soldiers.

Despite the difficulties inherent in his refusal to publicly support Hughes on the issue of conscription, Fisher made a valuable contribution to wartime liaison, particularly as a member of the Dardanelles Commission which was set up to investigate the Gallipoli disaster. For this work the French government awarded Fisher the Légion d'honneur, which he declined. Returning to Australia in 1921, he moved back to England the following year. At age 66, survived by his wife, a daughter and four of his five sons, Fisher died at his home in South Hill Park, London on 22 October 1928. After a state funeral at Hampstead Cemetery, London, he was buried there. The electoral Division of Fisher, in Queensland, was named in his honour, as was the Canberra suburb of Fisher, in which the theme for street names was Australian mines and mining towns.

- Biography written by Carmel Meiklejohn with reference to:

- DJ Murphy, 'Fisher, Andrew (1862–1928)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fisher-andrew-378/text10613, accessed 21 May 2012.

- National Archives of Australia, 'Andrew Fisher', Australia's Prime Ministers, http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/fisher/index.aspx accessed 26 October 2012.

- Clem Lloyd, 'Andrew Fisher', in Michelle Grattan (editor), Australian Prime Ministers, New Holland Publishers, Sydney, 2009.

- Parliamentary Library, Department of Parliamentary Services, 43rd Parliament: Parliamentary Handbook of the Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2011.

- In the first federal election in 1901, conducted under existing laws in each of the States, women had been able to vote only in South Australia and Western Australia. Commonwealth franchise and electoral laws passed in 1902 applied at the second election on 16 December 1903.